“Your submission has been rejected due to possible copyright infringing material.”

If you’ve ever received the above message from your digital distribution provider, you know how dispiriting and confusing it is.

The rules of copyright can be confounding – and infringement can have severe consequences. In the latest of a string of high profile cases, all royalties from Ed Sheeran’s monster hit “Shape of You” have been frozen, as a result of accusations of copying the chorus from Sam Chokri’s 2015 song “Oh Why.”

So how do you prevent getting sued or rejected due to copyright infringement? What are the rules? What can you use? Does it matter if you can prove that you never heard the track in question?

In this article I’ll go through everything you need to know to clear pre-existing material in your music.

The first question to ask yourself is: which part of a record am I using – the composition, lyrics or recording (sampling)?

The composition: singing from the same hymn sheet

Once a song has had its first release, anyone can cover that song without asking permission. As long as you credit the writers and don’t change the song, you’re in the clear.

But incorporating part of someone else’s melody into your own composition requires permission.

Incorporating part of someone else’s melody into your own composition requires permission.

Despite what many songwriters believe, there’s no set number of notes that are acceptable. The emphasis tends to be on whether the notes are identifiable enough with the other song.

If a dispute goes to trial, your song doesn’t even have to have the same melody for you to be guilty of infringement. When a jury decided that Katy Perry’s Dark Horse resembled Flame’s Joyful Noise enough to warrant giving them credits on it, Perry and her songwriting team and label were forced to pay out $2.78m, sending shockwaves across the creative industry.

Many argued that the part of the song that was deemed too similar was the arrangement – not the composition. Others pointed out that the note progression was also similar to loads of other compositions, some going all the way back to Bach’s violin sonata in F minor (adagio).

Similarly, the melody of “Blurred Lines” was nothing like Marvin Gaye’s “Got to Give It Up.” But the arrangement and vibe was similar enough for a jury to order Robin Thicke and Pharrell to pay the Gaye estate $5m.

It also doesn’t matter if you’ve copied another melody on purpose or not. Sam Smith and his co-writers claimed they had never heard Tom Petty’s “I Won’t Back Down” – yet they acknowledged that their song “Stay With Me” was similar enough to give co-writing credits to Petty and his co-writer Jeff Lynne.

Lyrics: not just text, but context

When it comes to lyrics, there is a bit more leeway.

If you search Spotify or Apple Music you’ll see that there’s no such thing as a unique title. It’s only if the lyrics are used in enough of a similar context or with similar notes to another song that you should ask permission and give credits.

A perfect example is Anne-Marie’s song “2002,” which credits a whopping 18 writers. This is due to its chorus, which includes lines such as: “Oops, I got 99 problems singing ‘bye, bye, bye’ / Hold up, if you wanna go and take a ride with me / Better hit me, baby, one more time,” referencing songs she was listening to as a young girl.

No prizes for figuring out which ones.

Sampling: clear it or lose it

Finally, sampling is a bit more clear-cut – as in, you should always “clear” them. This means that you have to contact the owner of the recording and the song for permission to use them.

If they say yes, you then negotiate how much of the copyright to your song you need to give them. Often you also have to pay them an up-front payment that can run into thousands of dollars.

Note that it doesn’t matter if you’re making money from the release or not. Claiming you’re only using the track for promotion does not exempt you from having to clear the sample.

Claiming you’re only using the track for promotion does not exempt you from having to clear the sample.

The length of the sample doesn’t matter either. Rapper Moses Pelham sampled a short drum sequence from Kraftwerk’s track “Metal on Metal” on his “Nur Mir,” and looped it.

Even though it was only a tiny sample, the court ruled in favour of Kraftwerk’s Ralf Hütter and against Pelham’s claim of “artistic freedom.” However, the European Court of Justice added that had Pelham manipulated the sample enough to make it unrecognizable, it wouldn’t have been infringement.

Still confused? Here are some basic rules to follow when sampling.

1. Keep a record

Make it easy for yourself by making sure that you keep track of who you’re sampling from, by writing it down when you do it.

Make it easy for yourself by making sure that you keep track of who you’re sampling from, by writing it down when you do it.

2. Get a sample clearing expert to clear it for you

It’s not always easy to know who owns a copyright, who to reach out to and how. The artist may no longer be alive, and the record may belong to their estate.

Even if they are, few people have artists like Tracy Chapman, Sting or Lauryn Hill on speed dial. Incidentally, you may want to stay away from sampling Sting if you want to keep a majority of your songwriting credit. The Police frontman famously demanded – and got – 100% of Puff Daddy’s “I’ll Be Missing You”, and 85% of Juice WRLD’s “Lucid Dreams.”

Remember that the clearance may only cover certain uses. Make sure you ask to clear it for “all audio configurations in perpetuity and worldwide.”

As you’ve probably gathered by now, clearing samples is a minefield. It isn’t something you should attempt on on your own without a lawyer.

3. Don’t forget to get permission from the songwriters/publishers as well as the artist/label

You need to contact both the owner of the recording (the master) and the song (the publishing).

You need to contact both the owner of the recording (the master) and the song (the publishing).

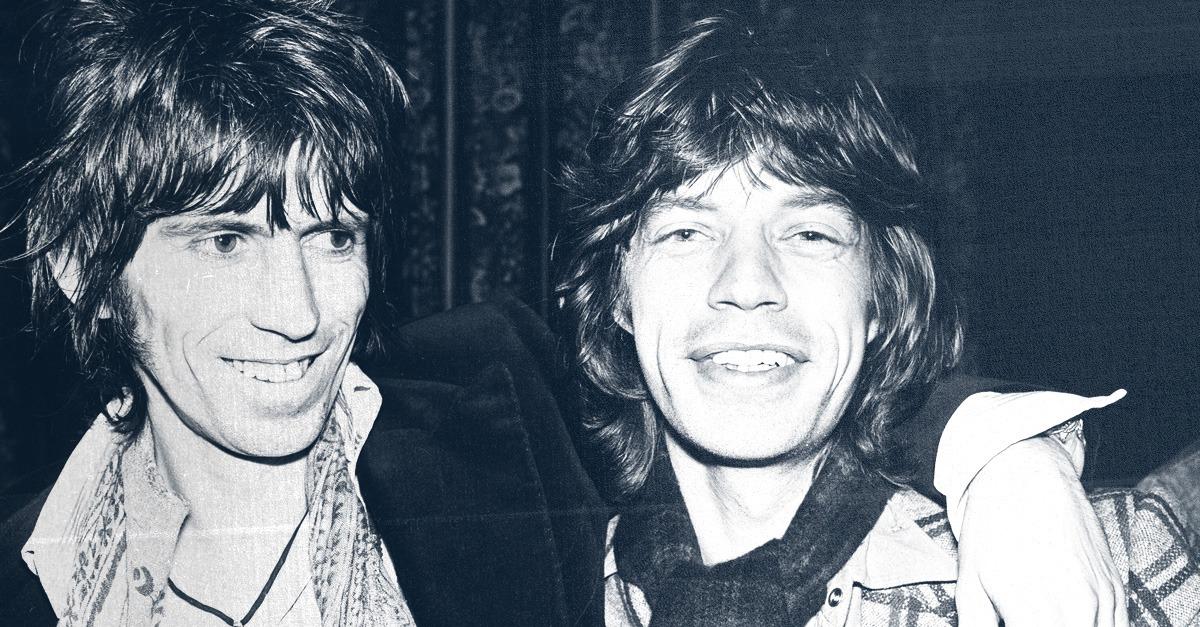

When The Verve sampled the strings from an Andrew Loog Oldham orchestral cover of the Rolling Stones’ “The Last Time,” they obtained the rights to use the six-note sample from the owner of the recording, Decca Records – but not from former Stones manager Allen Klein, who owned the rights to the song.

In the end The Verve had to give 100% of the songwriting credits to Mick Jagger and Keith Richards.

What might have happened if they had negotiated a deal before releasing the record?

Which brings us to the most important rule…

4. Clearing the way for a hit

Smart artists, such as Eminem, don’t take any chances and make sure every sample they use is cleared.

You may not bother to clear the sample, thinking that chances are slim that the artist you sampled will hear your track.

It’s true, no one bothers to sue over a track that only got a few hundred streams. But, conversely, as the music industry saying goes: where there’s a hit, there’s a writ.

Where there’s a hit, there’s a writ.

So if I could give you one piece of advice, it is to ask permission from the person you may have copied before you’ve released the record.

As The Verve learned, once a track is released, you have absolutely no leverage when it comes to splits negotiations. Before the release you can still threaten to take the sample off the track.

However, to make working with samples easier—and much cheaper—you can just subscribe to LANDR Samples and get access to millions of pre-cleared samples.

The added bonus is that you don’t have to share your songwriting credits with the creators of the samples—that means more revenue for your bottom line.